By Randy Haglund

The sirens began blaring their warning at noon.

They came from every direction. The closest one came from the corner of Central and “G” Street, two blocks west. It rose to a very loud and high crescendo and held its ominous tone for a few seconds before it descended. As it began its descent, the one at Alberta and Rowan—the opposite direction—rose to a high pitch. Then another one at Francis and Indian Trail joined in, undulating its haunting cry with the others. I heard sirens coming from all over Spokane moaning and wailing up and down for probably two minutes.

Then they stopped.

Dogs stopped barking. Birds warily resumed their chirping.

The feverish warning would have been cause for panic had it not been so predictable. Ever since I could remember the Civil Defense System would trumpet their alarm at noon on Wednesday. It was just another part of my childhood that seemed so normal—because it was normal.

If you grew up during the Cold War.

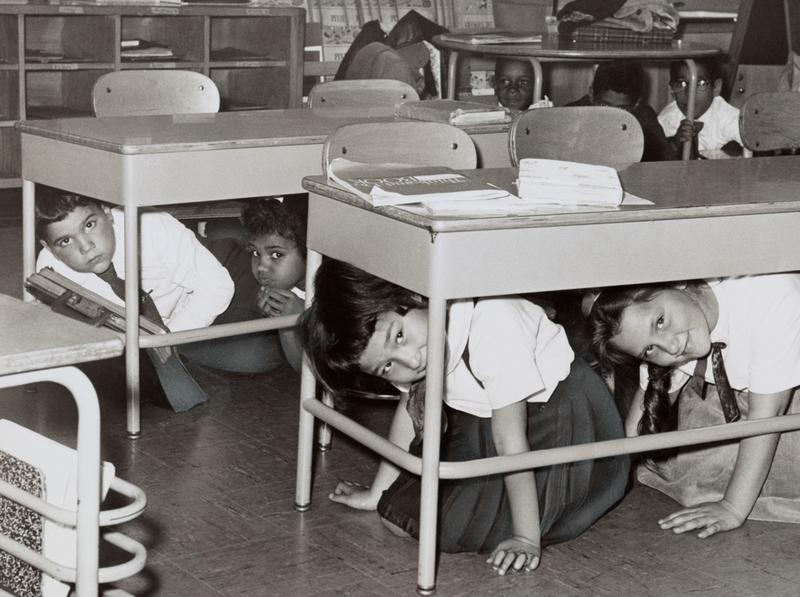

Another sign of the dangerous world I lived in came in the first grade, when I experienced my first air raid drill. We were told to duck down under the desk when the bell rang, and to stay there until it rang again. This procedure would protect us from a soviet attack.

So they said. It left me with scuffed pants and a sense of imminent doom.

I was too young to watch the news, but my parents had it on every evening so I watched it involuntarily. Playing with my Lincoln Logs on the living room floor, I tried to ignore the talking heads, but still deduced that grown-ups were gravely concerned about some crazy guy named Khrushchev and a Cuban Missile Crisis. My parents were worried.

A recurring nightmare plagued me during this time. It seemed very real and plausible, and always started with distant percussive sounds growing louder and getting closer. I looked out the window and saw a fifty-foot-tall giant (like the one in the Mickey and the Beanstalk cartoon) approaching. With an evil grin he crushed my neighbors’ houses underfoot, and mine was next.

I jerked up in a cold sweat. Then I would crawl up into the top bunk with my big brother Ricky. He wasn’t afraid of anything.

As I got older, I had a second nightmare. It began the same way, with the sounds of a giants’ footsteps getting closer, but when I peeked out the window, there was no giant. Instead, I saw wave after wave of airplanes dropping bombs on us. Startled awake again, I stared into the darkness with fear. I was too old to climb up with Ricky anymore.

Some of the people in the neighborhood built bomb shelters stockpiled with water, canned goods, and other imperishables in preparation for the inevitable nuclear holocaust. For the life of me, I couldn’t figure out why they went to all the trouble and expense when all they needed was a school desk.

My friends and I played “Cops and Robbers,” and “Cowboys and Indians,” just like earlier generations. But we had a new twist on it called “Man from U.N.C.L.E.” Based on a popular T.V. show, we were spies, determined to save the world from the evil organization T.H.R.U.S.H. Instead of arguing who would be good guys or bad guys, we argued about which one would be Napoleon Solo and who got to be Illya Kuryakin. (Everyone wanted to be Illya.)

By sixth grade the Cold War had become old news. I barely noticed the sirens still practicing every week. It seemed to me the Russians would be smart to attack at noon on a Wednesday. At any moment the two superpowers could blow us all into oblivion, but I couldn’t let that stop me from focusing on important matters.

Like playing soccer with my friends. Or listening to my Beatles records in the basement.

Growing up in the northwest part of Spokane meant we were right in the landing pattern for Fairchild Air Force Base. A strategic B-52 base, many considered Fairchild a primary target in case of a Soviet attack. Those colossal Stratofortresses flew low and loud overhead, rattling windows and some people’s nerves. But having seen them my whole life, I hardly even noticed them. Except I had to shout to be heard.

One time my cousin, Jill, visited us from a rural part of Oregon. We were playing badminton in the back yard when a big bomber flew over. She stopped and gaped. I asked what was wrong.

“I’ve never seen a plane fly over like that before!”

“Whadya mean?”

“Well,” she said, “whenever a plane flies over my house it’s just a dot with a white line behind it.”

Until then I didn’t realize how dull my senses had become to the daily reminders of the Cold War. But Jill’s rural lifestyle kept her in relative ignorance.

Must be nice.

In High School I had become cynical about the whole thing. Like most of my friends, we had become very anti-war and sick of all the rhetoric. Protest songs like Barry McGuire’s Eve of Destruction had long since become our anthems. But what could we do? We were just teenagers, helpless to alter the course of what seemed like a doomed future.

Then my oldest brother, Ray, returned from Vietnam and he was messed up. These days we call it Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. In those days some people called it Shell Shock. Others called it “Get Over It.”

Unlike the Cold War, Vietnam was a real war where the two superpowers battled on a neutral field. But they refused to call it a war at all. It was a “police action.” The United States never declared war. But with over 47,000 American casualties, it is rarely referred to as “The Vietnam Police Action.”

When Ray first came back from Southeast Asia I tried to get him to tell me some war stories. But he wouldn’t open up about it. Years later, when he finally did, I wish he hadn’t. He told me things I wish I could un-hear. No wonder he appeared on edge all the time. And I’m sure he kept many of the unspeakable atrocities to himself. Plus his exposure to Agent Orange while in Laos (unofficially) led to a number of other health issues. Ultimately, he too, became a casualty of the war.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 the Cold War thankfully came to an end, symbolized by the tearing down of the Berlin Wall. The world breathed a collective sigh of relief. Around the same time, the air raid sirens went silent for good and were eventually removed.

But is our life really different? 9/11 reminded us we still live in an unstable world. And now not just two countries have nuclear weapons. Nine do, and Iran is knocking at the door.

Growing up in the 60’s was definitely scary and weird. But do our children and grandchildren feel any any safer in today’s environment?

As it turned out, Barry McGuire was wrong. The 1960’s did not signal the end. Yet many have the same fears today. What about you? How do you cope with the possibility it all could come to a gruesome end any day.

Do you believe we are facing the Eve of Destruction?

Wow, memories I had forgotten! I do remember those air raid sirens…and the big bomber planes overhead. Bob and I didn’t realize you had an older brother who fought in Vietnam. Bob remembers those days as well and definitely relates to those stories that he too does not share.

These days…the enemies are within and without! Outside of the Lord, there are no assurances about anything. I’m so thankful we can stand on the Everlasting Rock—a secure and sure fortress in times like these. Psalm 91 has become a bedrock portion of Scripture I hold on to. Thanks for another great story Randy!

Amen, Verna. The world would be a scary place if we didn’t have the Lord. God has a plan, so I’m not worried.

That was so well written Randy. I was nowhere near as aware of our dire situation as a child. I do remember the sirens but I don’t remember ever feeling afraid. I’m so thankful Billy Graham invited me to God during those years.

Thanks Karen! I too am glad I met Christ in 9th grade. But it was only as an adult that I truly learned to put my trust in him and not to worry about the future.

Your description of what it was like growing up in Spokane during the Cold War was spot on Randy. Ducking under our school desks in case of thermo nuclear detonation was as ludicrous as putting on the gas masks that were so large they wouldn’t fit an extra large adult. Then we were instructed to bend over and put our heads between our legs. They didn’t say so but and kiss your ass goodbye. The noise the B-52’s made when they had an alert and scrambled into the air is something I’ll never forget. And yes, Fairchild AFB was part of the Strategic Air Command (SAC) and we would’ve been nuked in the first minutes of an attack. Kids today have no clue and I hope they never find out.

Thanks, Jim! Your response is the kind I’m looking for because you had similar experiences but different as well. We all had our own emotional responses and was good to hear from you.

Jim: I have heard (but not verified) that a certain percentage of the B52s had to be in the air at any given time during periods of particular tension with the Soviet Union, so that the whole fleet wouldn’t be caught on the ground in case of attack. That would be consistent with the planes I would see just circling around north of Spokane as a kid.

I never knew about that!

The B52s flew long missions up the coast, along the Aleutians, and flirted with he Soviet border. A friend of mine was a navigator and they always had crews on alert (imagine a fire station) ready to take off within minutes. He said there were occasional tests where crews flew to a way point near the border, then received orders to proceed to a jump off point to await the “go” signal. These were intended to assess crew response and readiness. He said some people would throw up from the stress of imminent nuclear war.

Great story, Randy (as always), and definitely brings back memories! I spent most of my elementary school years in the Tri-Cities, just outside the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, the only reactor that could arm our nuclear weapons back in the days. Thus, every time some unidentified blip showed upon the nearby radar, under the desks we went! Even in the second grade, we knew that desks were not going to protect us from nuclear weapons!

Since Hanford was where the nuclear warheads were actually armed with the weapons grade plutonium, periodically a train would pass through town, either bringing the unarmed warheads to Hanford or (I believe), taking the armed one back for installation in missiles, etc. Of course, the trains were supposed to be top secret, but enough folks around town worked at Hanford, plus the sudden increase in security, everyone knew at least the approximate days that the trains were passing through.

Most assuredly very interesting times!

That’s all new information to me, Evan. Thanks Evan!

Great story Randy. I remember those sirens and bombers well. The B52s would fly in formation; low and right over our house on Sutherlin St. So huge, they looked like they were just over the roof tops. I remember my dad digging a fallout shelter in the back yard (not sure he ever finished it). We knew about nuclear war and I remember reading Newsweek articles comparing China, the US, and the Soviet Union’s relative stores of bombs and missles and who had the most yield in kilotons of TNT. I got my draft card in the mail when I turned 18: 1A. But thankfully, the war ended the next year after a few years of US draw downs. I do wonder what the future holds for my children and grandchildren. The country seems more chaotic and divided than ever and I wonder if they will have the same opportunities we enjoyed.

Thanks for the input George. You have way more inside info than I do. I just remember the bombers flying low over head.

Thank you, Randy, for getting some Spokane memories going, about the drills and sirens, and huge warplanes overhead. “Eve of Destruction” was my favorite song for a long time. In 1959 I renewed my Spokane Library card at the Bookmobile parked outside of Westview Grade School, and when the nice lady wrote the card’s expiration date as July 1963, three years in the future, I was pretty sure the world would end before then!

I wonder what happens to kids when they feel the weight of an impermanent world? How about kids and young adults these days with the similar feeling of climate chaos over their heads? I hope they’ll handle the “Eve of Destruction” blues by getting active in fighting those forces that move us in bad directions, and insisting these directions are not inevitable. It’s what I try to do.

But also, I’m glad you brought up Ray. He was my age, lived next door, and was in a bunch of my classes from 1st grade on. We reconnected when he was home for R&R during the Viet Nam war. I knew he was against that war and he sent me some antiwar publications. It saddens me to read that such a nice man’s early death was a later casualty of that awful war.

Thank you for the strong essay, Randy.

Thanks Donna for the kind words and the commentary. That’s what my website is all about!