By Randy Haglund

This is part II of the true story of a wagon train on its way from Wisconsin to Washington Territory in 1878. Part I can be found here: On a Prairie Schooner. My ancestors (the Giffords) were in that party. (Note: No images of the wagon train are available. The above image is of Buffalo Bill Cody.)

TROUBLE IN WYOMING

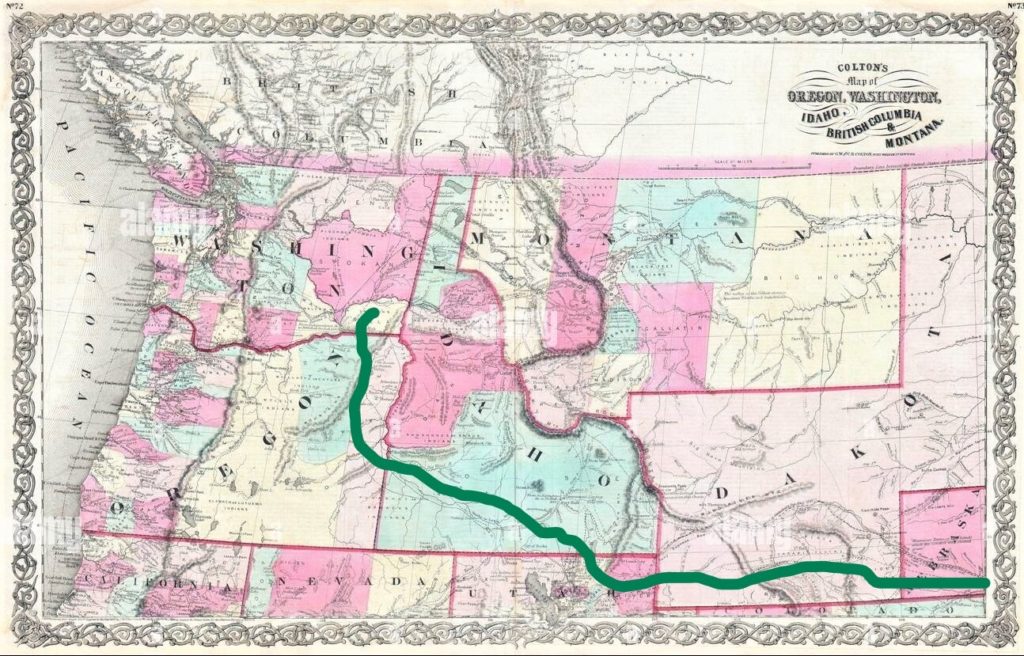

When the wagon train crossed the line on June 26, 1868, they technically crossed into Dakota Territory. Wyoming officially became its own territory twenty-nine days later, just before they left Wyoming and entered Utah (see map below).

Lucy described Cheyenne as a “nice bright lively western city.” It seems like a rather tame description for a town known for it’s wild west reputation. While there they witnessed the arrest of a murderous gunslinger by federal authorities, who fitted the outlaw with an Oregon Boot.

On the third of July they stopped at the top of Cheyenne pass (over 7,000 feet) and a snowball fight broke out in the middle of the summer. It was a perfect time for the party to break the tension of a long journey!

On the other side of the pass they came to Rock Creek where they found a toll bridge charging thirty-one cents a team to cross. Freezing cold from recent snows, the very rapid stream appeared to be unfordable. It seemed they had no choice but to pay.

Two days later they came to another toll bridge charging fifty cents a team.

Highwaymen!

Deciding to traverse the turbulent stream, which was difficult enough, the bullies made it even more dangerous by tossing railroad ties from upstream in an attempt to break the horses legs or the wagon wheels. After threatening the bridge owner with a gun, they managed to get across the stream without calamity.

Four days after that they came to another toll bridge — this time charging ten dollars per wagon! Heavy chains and a padlocked gate stood across the bridge. Large boulders had been placed in the creek, making it impossible to ford. Clint Gardner told the bandits if they wouldn’t let them pass, his men would tear down their bridge. Someone drew out a handsaw to show they meant business.

Two more sinister-looking men appeared wearing six-shooters and said, “Try it, and we’ll fill you full of lead.” But Clint pulled his gun, and then more weapons appeared from the wagon train. Outnumbered, the extortionists agreed to a more reasonable price of ten dollars total. “Nope. We’ve been put through more than ten bucks worth of trouble already.”

They crossed for free.

Consequently,for the next few nights, several attempts were made to steal the pioneers’ horses, but Clint’s gun prevented them all.

As the party passed through the beautiful Bridgers Pass on July fourteenth, the emigrants ran into a group of Princeton College students on a study of minerals, fossils and petrified woods. That evening they gathered together for a hymn sing.

Lucy described it as a glorious evening of worship as they sang the songs of D.L. Moody and Ira Sankey. To us they seem like old fashioned hymns, but in the late 1800’s these were the new songs from the Moody crusades. Songs such as Nearer My Go to Thee, Room in My Heart for Thee, and The Love of Jesus resounded in the mountains and lifted the spirits of the company.

When the train reached Green River on the eighteenth of July it was the first town they had seen since Laramie — three hundred miles and two weeks.

MORMON COUNTRY

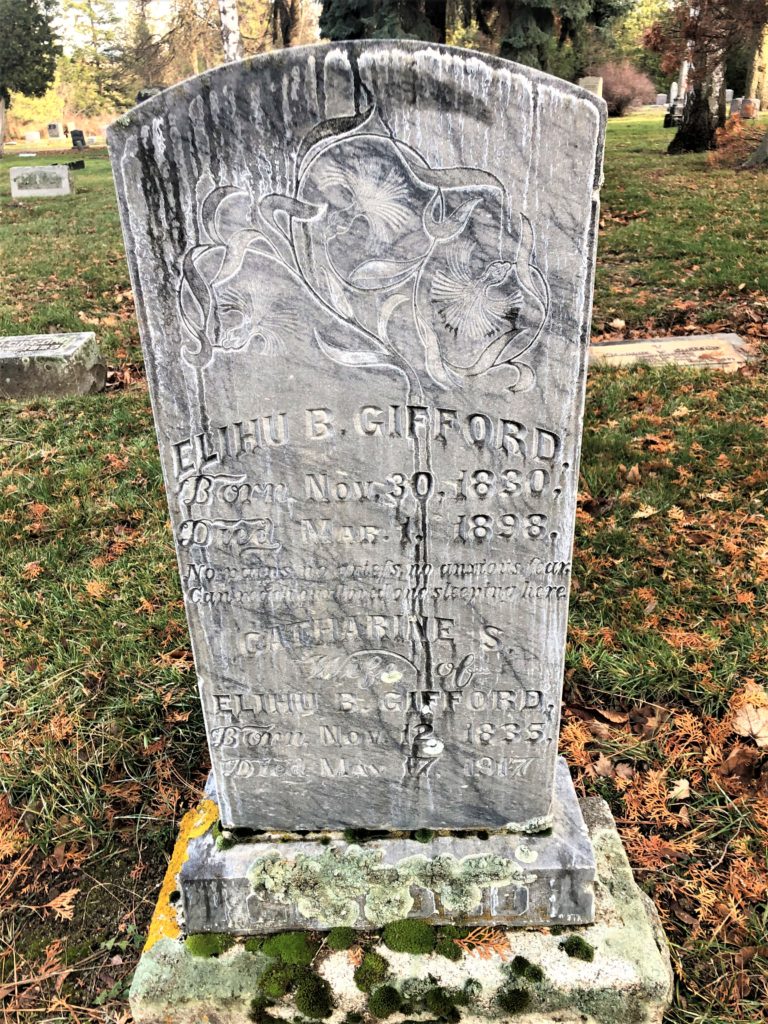

Coming down the steep and narrow Echo Canyon into Utah on the twenty-sixth of July, they experienced a total solar eclipse. This astronomical event was accompanied by a maternal one. Edith Gifford – Elihu’s daughter-in-law – gave birth to a boy, Homer, at the foot of the Wasatch Mountains.

The family must have known she would give birth somewhere along the Oregon Trail long before they left Mondovi. Yet they chose to not delay their journey. Despite facing primitive conditions, they trusted God would bring them safe passage, as well as the baby.

After the emigrant train stopped at a hot springs near Corrine, Utah they stayed overnight at a ranch where some of the wagons had their “tires sett.” Periodically the “tires” on these prairie schooners needed tightening. This refers to the steel band running around the perimeter of the wooden wheel. Over time they would get loose and required attention. Apparently the ranch had a wheelwright that could do the job.

Here they had to make a big decision. People were deserting the area because of hostile Indians burning down houses and otherwise destroying property. Some people said the “Injuns” were murdering white people up ahead. Some of the sojourners were afraid and wanted to go back to Ogden and settle there. They stayed an extra day to think things over, and as a group, decided to press on.

FEAR AND INDECISION IN IDAHO

Soon the emigrants were in southern Idaho Territory. The long haul had tired some of the horses out and they had to be traded. When they came to Marsh Basin (now Albion, Idaho), some of the young women were offered jobs in a local hostel. After some consideration, everyone committed to continuing on.

Lucy complained of going miles and miles over dusty roads with nothing to see but sagebrush until they crossed the Snake River at Payne’s Ferry. At this point the roads got better as they were used extensively by stage coaches going to and from Boise and northern Utah. Here she marveled at some “Bridal Veil” waterfalls and springs (today called Thousand Springs State Park). After crossing the 300-foot-deep Malad River gorge the wagon train ran into an old friend from Winona taking a stage coach. It was good to see a familiar face.

Deep in Indian territory now, where they were on the warpath, they came upon a man and his family whose four horses had been stolen by Shoshones. Lending him horses, the man and his family ended up staying with the party all the way to Walla Walla.

By camping close to stage coach stations they felt a bit safer from Indian raids, sometimes seeing troops of soldiers engaged as scouts and Indian fighters. By the time they reached Boise, they felt like they had finally come to a secure haven.

But a couple families were lured away from the train with offers to work here. A business owner of some kind offered Chet five dollars a day and Lucy two bucks a day to stay. Out of money, the couple decided they would give Boise a whirl. Elihu tried to get them to change their minds but to no avail.

After tearful good-byes the train left them with their goods at the station. But fifteen minutes later Elihu came riding back into town on a horse like the Lone Ranger.

“We’re not going to let you stop here! Get your stuff and let’s go!” The Ides were having second thoughts after all. and got back in their wagon and caught up with the rest. Which is a good thing because if Lucy would’ve stayed in Boise they would’ve lost their diary-keeper.

Two days later they crossed the Snake again on another ferry and were in the state of Oregon.

THE UPS AND DOWNS OF OREGON

The cattle ranches in Oregon appeared prosperous but once again they feared Indians, who had recently stolen horses and other livestock in the area. Alas, their anxieties were for naught. The pioneers encountered not a single Indian conflict for their entire journey.

After passing through Union and Summerville they began the 2,500 foot climb over the Blue Mountains. The scenery was grand, but one of the women became very ill. Camping at the summit, Lucy tended to her all night. The woman had been suffering on much of the journey but that night her consumption (tuberculosis) had especially flared up.

She believed she was about to die, and everyone else did too. Lucy applied warm damp cloths to her chest, which brought some relief, but it made for a long night for everyone. The next day Lucy kept by her bedside in her wagon as they made their slow descent down the other side. With each mile the woman felt a little better.

THE LAST LEG

Finally they crossed into Washington Territory. After getting supplies in Walla Walla, the emigrants rested for a day. While there they saw “a great many Indians,” but they were friendly. Two days later on September 15, 1878, they arrived at their final destination in Dayton, to be greeted by Dr. Day, their friend from Mondovi. Handshakes and celebration ensued. They camped in a cottonwood grove on the shore of the Touche River.

Four-and-a-half months of trials, joys, tribulations, fellowship, scares, and adventure were behind them. As far as I know, there is no record of any one of the prairie schooner pioneers regretting their decision to take the Oregon Trail West.

From Dayton the families of the expedition settled in various places in eastern Washington over the years. Some stayed in the Dayton area, some came up to Spokane and other parts of the state. My family — the Giffords — settled in Whitman County not far from Rosalia. Later they came up to Spokane, but not before a brief time in what is now Lincoln County. There, Elihu formed another new town. He called it… Mondovi.

Guess he really liked that name.

***

What about you? Have you got any stories about your ancestors? Let’s hear ’em!

Fascinating story!

Thanks, Dave!

Love your story

Thanks, Anita!

I’ve driven by Mondovi and thought “what the heck”. Wondered how it got there.

Well, Bob. Now you know. It was my great great grandfather. He had a thing for history.

Randy

I really enjoy reading your stories about Pioneer days. Thank you. My 3rd g -grandparents came from Iowa on a wagon train to the Dixie, WA. area in 1863. They had a stagecoach stop 2 miles north of Dixie. Their future son-in-law came from Iowa to the California gold fields in the mid-1850s. He worked his way north until he landed in Walla Walla. For a short time, he was a Pony Express rider from Walulla to Colville. Then, he was a stagecoach driver from Walla Walla to Lewiston. Busy guy. After marrying, he settled in the upper Tucannon River valley in Columbia County where he had a stagecoach stop. He and his wife are buried in Pomeroy. (Keep those stories coming.)

Thanks, Kay! It looks like your pioneer ancestors covered the same ground as mine! Very interesting!

Randy

Ron, fascinating Gifford family history ! My children are paternal descendants of William GIfford of Sandwich, Massachusetts, also an ancestor of your Elihu Gifford. I came upon your website page after working on WikiTree profiles for Elihu Gifford and his family. I have since added his photo with links and credit to your web page. You can add to Elihu and his family profiles, I can also add you as manager of their profiles, membership to WikiTree is free and well worth it ! Please contavct me if you have questions: https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Gifford-4324

Sandie, thank you for that reply. Very interesting! As a shirt-tail relative, I am of course interested in Wiki Tree. I am not familiar with it, but I have done quite a bit of research in the family tree on Ancestry, including all the way back to Sandwich. I will indeed look into it. Thank you.