By Randy Haglund

In the summer of 1878, my great-grandfather, Elihu B. Gifford, had a vision. He and a group of families departed from Mondovi, Wisconsin by wagon train on a journey to Washington Territory. It was a perilous journey, with the hope of prosperity at its end. This is the story of their migration.

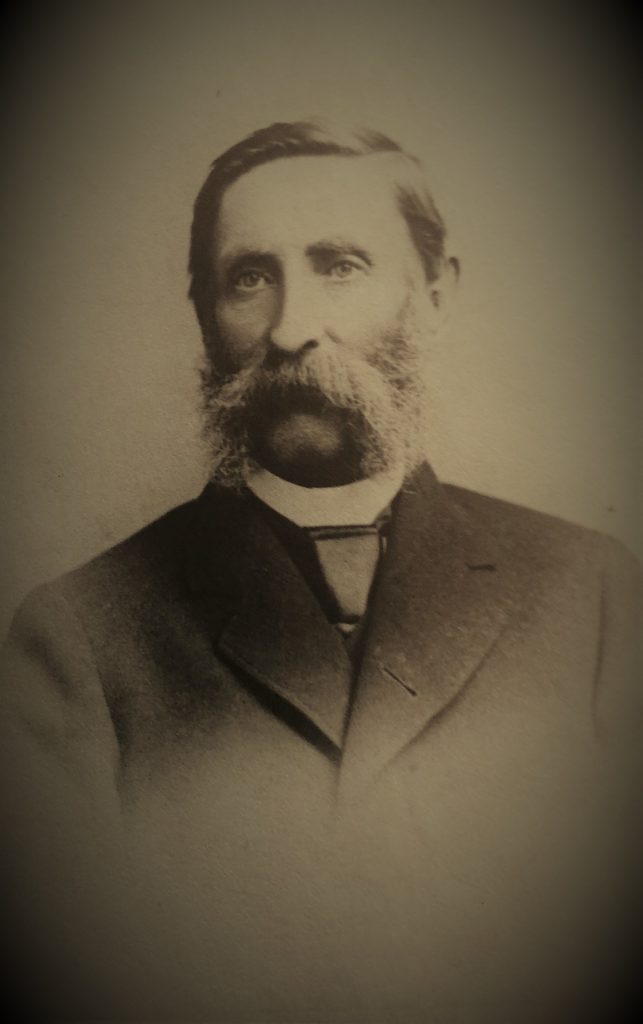

Born in Greenfield, New York in 1830, Elihu took his wife, Catherine, and their one-year old daughter to Buffalo County Wisconsin. Land was about one-sixth the price of property in eastern New York. Not long after settling, he was appointed chairman of a committee to form a township there, and Elihu named the town Mondovi, after a famous Napoleonic war battle in northern Italy (he was a history buff). His wife gave birth to a son, John, soon thereafter, the first white child born in Mondovi.

Along with his friend, Chester Ide, Elihu opened up Mondovi’s first hotel.

After twenty-two years, the Giffords and other families kept hearing stories about prospects in Washington Territory. Dr. W.W. Day (formerly of Wisconsin) had settled in Dayton, Washington Territory recently. He wrote letters back to his friends in Buffalo County, describing the soil as “rich, deep and very productive.” He claimed it yielded grains, vegetables and fruit in abundance. And a man could homestead as much as 480 acres! His assertions of the Palouse’s profitability were difficult to ignore.

The Willamette Valley in Oregon had been the favorite destination of settlers in previous years, and by the 1870’s it was fully inhabited. But the potential of the Palouse had not yet been exploited. Dr. Day warned them that if they didn’t come soon, they would miss out on a chance of their lifetime.

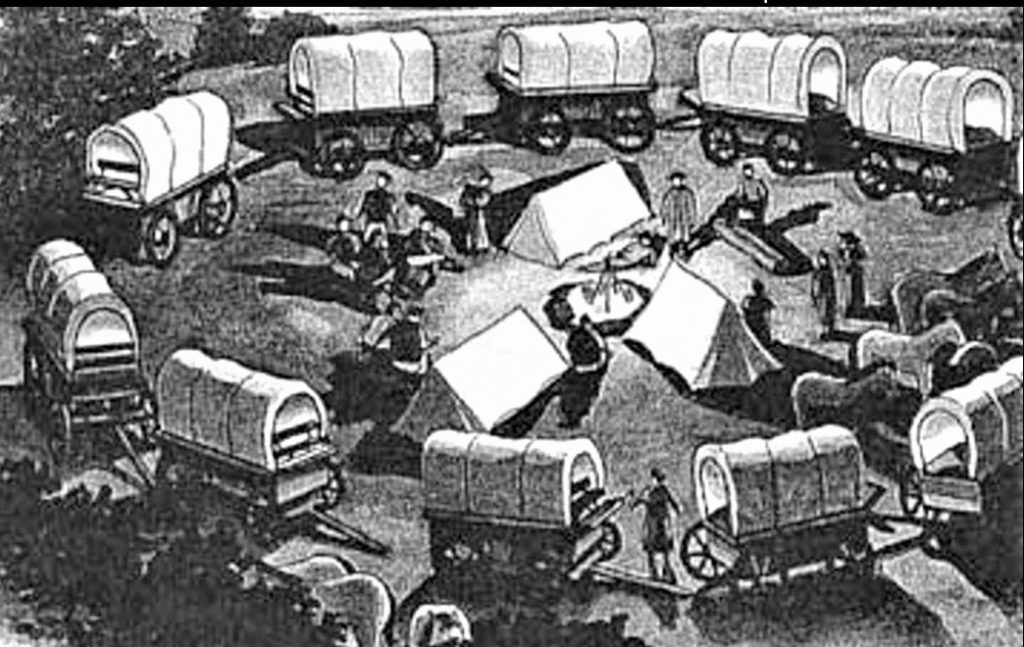

So Elihu organized a group of friends — about forty in all — to make the ambitious move to Washington Territory.

But why wagon train?

The Transcontinental Railroad had been completed about nine years earlier. And the Oregon Trail was fraught with perils such as Indian raids, breakdowns, and the exceeding hardships of traveling in those days.

We can only speculate as to the reasons leading to their decision. So let’s do that.

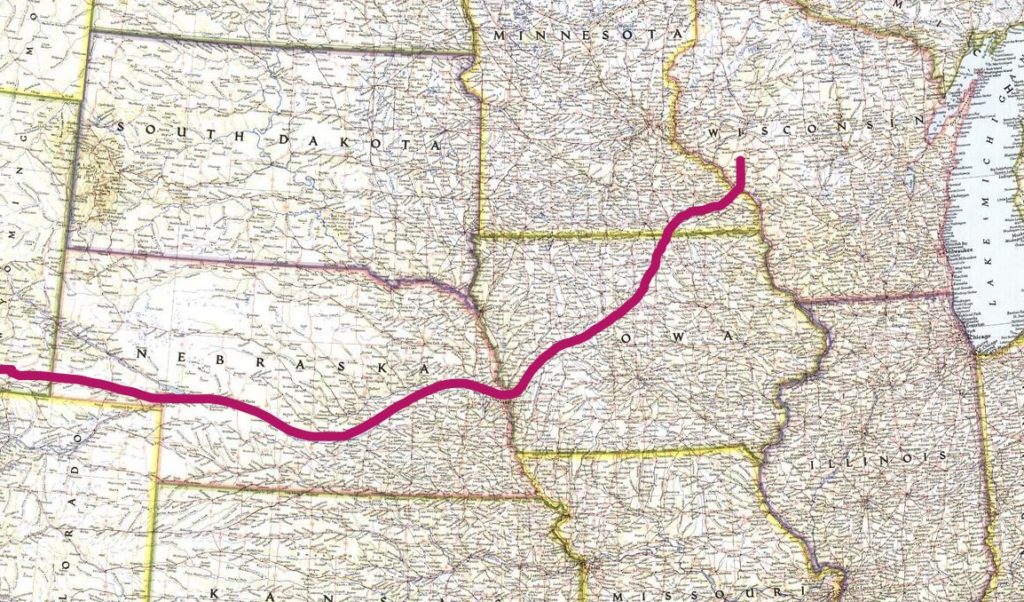

For starters, the railroad didn’t come to Mondovi, though it wasn’t far to Eau Claire. From there it seems they would’ve had to go east to Chicago. Then they could’ve traveled to Omaha to hook up with the Transcontinental Railway.

Rail, however, wouldn’t get them to Washington Territory. To get there, they would have had to travel to San Francisco, take a steamer ship up the Pacific Coast to the mouth of the Columbia River and on to Portland. After that, they would have to take a series of barges up the wild Columbia to Wallula. Then they were still more than sixty miles from their intended destination.

The practicality of taking a large group and their belongings on such an excursion may have been prohibitive. And that’s not even taking expenses into account.

On the other hand, by taking a wagon train, the group could bring along their valuable horses and some cattle. They could also bring some small appliances, household goods, as well as heirlooms and such.

But I’d like to think that a big reason for the decision was the adventure. I picture Elihu B. Gifford as a man that wouldn’t back away from a challenge.

Yet it would take a heap of preparation and planning. There were no convenience stores along the way. They would need to save room for hundreds of pounds of food supplies such as water, flour, bacon, hardtack, corn, rice and salt. Shovels, axes, and cooking utensils would also be necessary. And they would need money. And guns.

And hearts of steel.

UNDERWAY

On May 1, 1878 the families said goodbye to Mondovi and headed south to the Wisconsin/Minnesota line. The wagons and tack were new. The horses were fresh, the teams weighing from 1500 to 1600 pounds each.

Clint Gardner, a seasoned gunman, was dubbed their wagon train leader. He had previous experience on the Oregon Trail.

Lucy Ide, Chester’s wife, took on the responsibility of keeping the diary on the wagon train.[1] I’m sure she spoke for everyone when she said “The hardest of all is bidding farewell to my near and dear friends many of whom I fear I have seen for the last time on earth…It is almost more than I can bear.”

It was cold and snowing as they crossed the “toe” of Minnesota. Except when it rained.

After ten days of traveling they crossed into Iowa where they ran into their first trouble. The poor roads were made worse by the recent rains. Numerous times wagons got stuck axle-deep in the mud. Many hands and the presence of plenty of horses and oxen helped get them unstuck. But before long they’d be mucked in again. It was slow going.

And some were already starting to have second thoughts. After a severe thunder storm they had to spend a day repairing leaks and drying out bedding and such. Long faces abounded.

ON THE OREGON TRAIL

On the 28th day of May they loaded their wagons and livestock onto railroad cars and crossed the muddy Missouri River on a railroad bridge into Omaha, Nebraska. Now they were officially in the Wild West! Here the Oregon Trail ran parallel to the Platte River and the Transcontinental Railroad. They remained within eye contact of the tracks throughout much of Nebraska and Wyoming, and even into Utah.

In central Nebraska, some of the men went jack rabbit hunting. One of Elihu’s bullets went astray, ricocheting off the ground and striking a steer, breaking its leg. You can imagine the ribbing he got for that. The next day the local sheriff came and arrested him and put him in jail. Seems that the owner of the steer wanted a lot more for his loss than Gifford was willing to pay. So the farmer sicced the local sheriff on him.

While languishing in his cell Elihu got to talking to the sheriff and it turned out that the lawman was a brother to one of Gifford’s old friends back in Mondovi. They chatted it up for a while and the sheriff decided Elihu wasn’t so bad and let him go after paying twelve-and-a-half bucks. That night they didn’t have rabbit stew, they ate beef.

The following night a terrible thunderstorm came through. As they discussed camping in a beautiful meadow, storm clouds moved in, and they decided to move to higher ground about a quarter mile away. They circled the wagons as usual, but chained them together as the fierce thunderstorm came with high winds and angry lightning. Elihu stayed up to tend to a sick horse, and few others got any sleep that night. The terrified horses stomped and flared their nostrils.

In the morning Elihu announced that his horse had died. The sad news was buffered by the relief that they had moved their camp the night before. They could see below the meadow completely under water, and the railway bridge had washed away. As they traveled west, Lucy counted twenty-five consecutive telegraph poles taken out by lightning, and four horses found dead along the trail, also struck by lightning.

One Sunday some of the younger folks decided to dress up in their best bib and tucker to attend church. As they arrived they could hear congregational singing. Someone remarked, “Just in time.” So they marched in and up to the amen corner and when the singing stopped they prepared to sit down. But the congregation remained standing for the benediction. Not until then did they realize they had crossed from Central into Mountain Time Zone the day before, so they actually missed the service.[2]

Further west in Nebraska, a stray pony came along and it turned out to belong to the famous showman, Buffalo Bill, whom they met when they got to the next town, North Platte. He was grateful to have it returned.

On the 25th of June they caught a glimpse of the Rocky Mountains for the first time. Nearing the Wyoming border, they were delighted to be leaving Nebraska, which they had become bored with. Little did they know what lay ahead.

***

Check out the exciting conclusion of On A Prairie Schooner next month right here on Allegedly True Stories.

[1] Her original diary can be seen today at the Eastern Washington Historical Society, and is my primary source for this story. Some additional information is found in the volume entitled Ancestry and Descendants of Ezra Sisson and Amelia Plemon, by Raymond Olson (my uncle).

[2] This story is related by George Baker, another member of the emigrant train. Other details of the journey are also gleaned from his recollections. Found in the Dayton Chronicle-Dispatch Sept. 14, 1933.

Geat story! Wonderful that you have family history right at your fingertips! What a privilege!

Thanks, Verna. I hope you catch up next month for the conclusion that brings us right to Spokane!

Thanks Randy, great to know your family history. I know my great grandparents came to Spokane in the late 1800s from Sheridan Wyoming. Grandma Jaques parents.

That’s cool! Did they settle in Morgan Acres, or somewhere else?

We’ll done!. I think there just might be a novel lurking within this fascinating family history.

You are right! I plan on it in the future. Thanks for the input!

Your usual excellent writing Randy – look forward to reading the conclusion to this saga!

Thanks, mother-in-law! I believe you are coming from a completely unbiased point of view!

This is so well written. I found myself along the trail with these people. You wrote and situated it feels real. I can’t wait to read the next installment

Thanks, Karen. I’m glad you enjoyed it. More perils ahead!

This is so well written. I found myself along the trail with these people. You wrote and situated it feels real. I can’t wait to read the next installment